“What’s it like to live in a bubble? For some, this means living a sheltered life. But David Vetter, a young boy from Texas, lived out in the real world — in a plastic bubble.”

Born in 1971 with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), David was nicknamed “Bubble Boy” — from birth, he lived in a specially constructed sterile plastic bubble. Why? Due to SCID, he did not have a working immune system, and was highly susceptible to life-threatening infections by viruses, bacteria and fungi. The sterile plastic bubble protected him from those infections. He lived in it until he died in 1984, at age 12, following an unsuccessful bone marrow transplant — an attempt to provide him with the capacity to fight infections on his own, and become a bubble-free boy. These days, there is hope for children born with SCID — thanks to new therapeutic approaches, and thanks to population-wide newborn screening programs.

Image credit: Josh Kenzer, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

SCID is an inherited disorder caused by defects in any of several possible genes — these genetic defects lead to severely impaired immune responses. The impairment involves both T and B cell responses, hence the term “combined.”

According to the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), the most common type of SCID is called XSCID because the mutated gene, which normally produces a receptor for activation signals on immune cells, is located on the X chromosome. Another form of SCID is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA), normally produced by a gene on chromosome 20.

The classic symptoms of SCID include an increased susceptibility to a variety of infections, including ear infections (acute otitis media), pneumonia or bronchitis, oral thrush (a type of yeast that multiplies rapidly, creating white, sore areas in the mouth), and diarrhea. Because children with SCID experience multiple infections, they fail to grow and gain weight as expected (i.e., failure to thrive). Children with untreated SCID rarely live past the age of two.

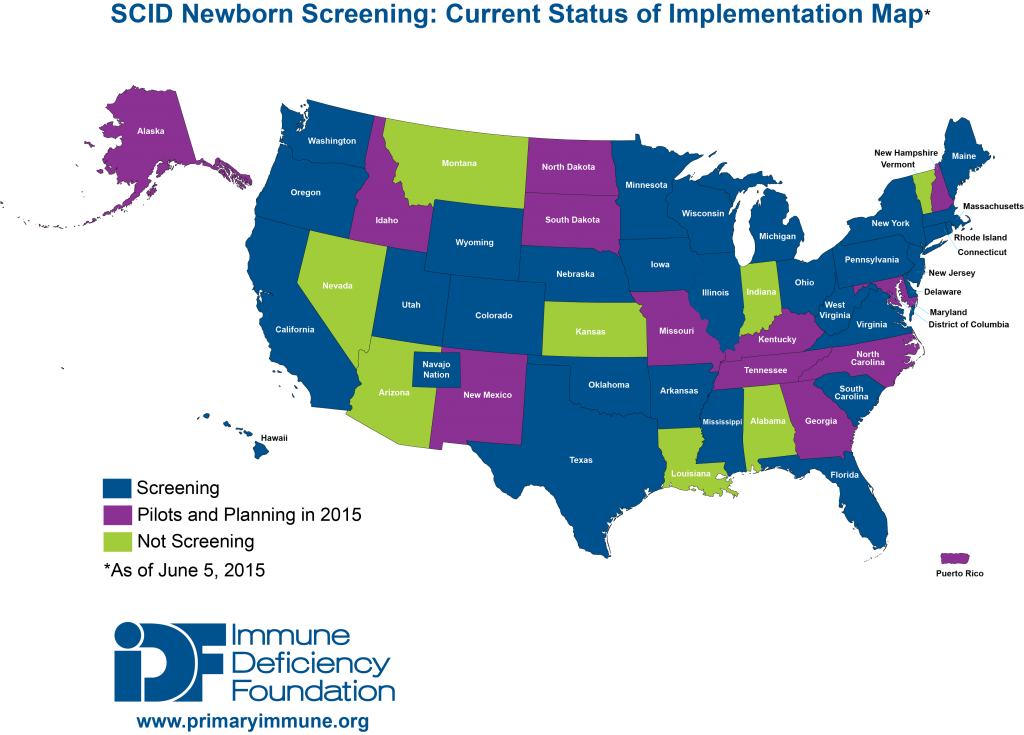

NHGRI states that there is no central record of how many babies are diagnosed with SCID in the United States each year, but the best estimate is somewhere around 40-100. So, SCID is a rare condition. On the other hand, researchers have no clear idea of how many babies are not diagnosed and die of SCID-related infections each year. Thus, NHGRI points out that the actual number of cases could be higher. Indeed, results from a study published in 2014 — the first to assess the national impact of the disease — show that severe combined immunodeficiency, called SCID, affects 1 in 58,000 newborns, instead of 1 in 100,000 as previously estimated on much more limited data. The study analyzed results from 11 newborn screening programs. At the time the study was carried out, 23 states, the District of Columbia, and the Navajo Nation were conducting population-wide newborn screening for SCID.

Newborn screening programs enable early detection of conditions for which prompt treatments can reduce the risk of death or irreversible damage. Early detection is critical for treatment of SCID and, in most cases, population-based testing through newborn screening programs is the only means to detect SCID prior to the onset of infections. Thanks to recent advances in stem cell transplantation, early detection holds the promise of a normal, healthy life for children affected by SCID.

Beverly Hay, one of the study’s authors, said in a press release: “The incidence of SCID was found to be higher than previously estimated, suggesting that SCID was likely under-recognized and underdiagnosed in the past. Early detection allows for treatment before a child becomes overwhelmingly ill, which leads to a better outcome for that child.”

Jennifer Puck, another study’s author, told SFGate: “”If you don’t find them, you can’t treat them. If you do find them, you give them a transplant and make them into a healthy taxpayer.”

Below is a map — from the Immune Deficiency Foundation — showing the States currently screening for SCID (as of June 5, 2015.)

This is an updated version of a post that first appeared May 16, 2015, on Immunity Tales, and has been reproduced here with permission.

Newborns with SCID usually appear normal at birth as the babies are not exposed to infections, it is not until the onset of infections and complications that the diagnosis is done. Due to the costly screening methods the diagnosis of SCID in newborns is not done on a regular basis. However, with the advent of automated high throughput sequencers this trend may change soon.

“Gene diagnosis” is the best method available today for SCID fetal diagnosis and carrier identification. This method looks for the presence of certain gene mutations in the fetus or the parental genome. For example to detect the presence of X-SCID the fetus/parental genome is checked for any mutations in the interleukin-2 receptor gamma (IL2Rγ) gene. These mutations are then matched with the data available in the Human Gene Mutation Database. This database contained about 200 mutations in the IL2Rγ gene until 2014. This database is updated as novel mutations in IL2Rγ are discovered.

Prenatal diagnosis or carrier identification can help in accurately identifying fetal situations and can be used to avoid birth defects, which can also ease the anxiety of the pregnant mother, and help in reducing costly hospitalizations leading to better outcomes.

Source:

Bai QL, Liu N, Kong XD, Xu XJ, Zhao ZH. Mutation analyses and prenatal diagnosis in families of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency caused by IL2Rgamma gene novel mutation. Genetics and molecular research : GMR. 2015;14(2):6164-6172.