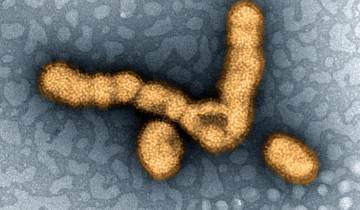

Tuberculosis — or TB for short — is a modern disease, known since ancient times. It is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an exclusive human pathogen. According to the World Health Organization, in 2013, nine million people fell ill with TB and 1.5 million died from the disease worldwide.

Although it is difficult to estimate the number of deaths caused by TB throughout history, we know that M. tuberculosis has been an ever-present scourge for humanity, and may have killed more people than any other microbial pathogen. Indeed, TB has been given many unpleasant names. From Hippocrates through to the 18th century, it was known as phthisis and consumption. During the 19th century, TB was called the white death and the great white plague. Other “historical” TB names aptly evoke images of despair and horror — the robber of youth, the captain of all these men of death, the graveyard cough, and the king’s evil.

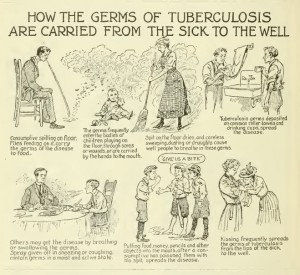

Image credit: Government & Heritage Library, State Library of NC, CC BY 2.0

The long-standing relationship between M. tuberculosis and humans has been present not just for a few thousands of years, but for much longer. In 2013, researchers “found evidence that TB hitched its cart to the human evolutionary horse more than 70,000 years ago, before our ancestors migrated out of Africa.” They published their findings in the scientific journal Nature Genetics. Sebastien Gagneux, an infectious diseases specialist at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute in Basel and senior author of the study, said: “The old, traditional view was that tuberculosis emerged during the Neolithic transition when people started to domesticate animals and develop agriculture, which started about 10,000 years ago. Our work suggest that TB is really much older.” The researchers explained in their paper that different strains of M. tuberculosis accompanied migrations of modern humans out of Africa, and expanded as a consequence of increases in human population density during the Neolithic period.

Between the 17th and the 19th century, TB caused about 20% of all human deaths in the United States and in Europe. Until the early 20th century, people infected with tuberculosis were isolated from society and placed in sanatoriums — self-contained communities that, not surprisingly, became known as “waiting rooms for death.” Now, a new study published in the journal Nature Communications, reveals how TB took hold in 18th century Europe. The researchers analyzed samples from mummies found in a Hungarian crypt, and found evidence of multiple tuberculosis strains derived from a single Roman ancestor that circulated in the 18th-century. Mark Pallen, senior author of the study, said in a press release: “Microbiological analyses of samples from contemporary TB patients usually report a single strain of tuberculosis per patient. By contrast, five of the eight bodies in our study yielded more than one type of tuberculosis — remarkably from one individual we obtained evidence of three distinct strains.”

The samples originates from a crypt, re-discovered in 1994, located in the Dominican church of Vác in Hungary. It contained the remains — which had undergone natural mummification — of over 200 individuals, mostly affluent Catholics from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

The researchers used a technique called “metagenomics” to identify TB DNA in the historical specimens — the technique draws on the remarkable throughput and ease of use of modern DNA sequencing technologies, and allows sequencing of DNA directly from samples, without the need of growing bacteria or deliberately fishing out TB DNA. The researchers found that the samples carried the genetic signature of M. tuberculosis Lineage 4, a strain that today accounts for more than a million TB cases every year in Europe and the Americas.

Pallen said: “By showing that historical strains can be accurately mapped to contemporary lineages, we have ruled out, for early modern Europe, the kind of scenario recently proposed for the Americas — that is, replacement of one major lineage by another — and have confirmed the genotypic continuity of an infection that has ravaged the heart of Europe since prehistoric times.” He added that the struggle to contain TB is far from over, and concluded: “We have shown that metagenomic approaches can document past infections. However, we have also recently shown that metagenomics can identify and characterize pathogens in contemporary samples, so such approaches might soon also inform current and future infectious disease diagnosis and control.”

It is fascinating to me to learn that Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or TB, has evolved with humanity from generations long past! In a way, it was on that fateful day that the first human was colonized by TB that I wonder if the organism itself had a choice, to kill or not to kill? It may seem weird to think about, but what if TB could have instead worked with our cells instead of against them to become a natural component of our bodies? The first response to this thought might be, “That’s absurd! There’s no way that could even happen! No organism that thrives by killing our cells would be able to peacefully coincide with them!” However, this natural retort may not be as true as some take it to be. Remember back to the beginning lessons of biology, where it was taught that a specific component of the cell, the mitochondria, shows evidence of being an external organism before becoming a part of our cellular structure. This idea is called the Endosymbiosis Theory, which states that because Mitochondria, and even another cellular component, the Chloroplast, have their own set of DNA and replicate differently then other parts of the cell, it is thought that these components were at one time their own organism that became engulfed by our cells and instead of struggling to lyse their way free, assisted our cells and became the “powerhouse” component scientists know today. However, it took billions of years for this symbiosis to occur and become the association that fundamentally furthers our cellular structure. Although that may seem clearly obvious that a symbiotic relationship would take massive amounts of time to create, is that not exactly what TB has had decades of time to create? If instead of becoming a pathogen that infects and then kills our cells TB had become a natural component of the immune system, per say an intracellular component of the macrophages it used to infect that helps to recognize similar pathogens and then lyse them before they can create a problem, wouldn’t that be astounding? This former pathogen could help form a superb immune response that prevents a wider variety of harmful pathogens from ever taking hold inside macrophages, because it itself already has that hold! Not only that, it’s nurtured by our cells and has the comfort and security of nutrients, allowing for a spectacular case of symbiosis! What if instead of eradicating TB, one was able to tame it? Before you, the reader, outright reject the thought, consider this next thought. TB has evolutionarily grown beside humans as one of the greatest diseases mankind has ever faced, and yet also become so entwined with mankind that it only infects our species! This means that it knows our cells very well and could potentially be able to naturally become a part of our cells, given that its developed so much alongside our cells, albeit to harm them instead of hurt them. Could there not be a way to instead reprogram TB to work inside our macrophages and allow it to become a natural part of the immune system by preventing other pathogens from taking residence inside macrophages? Although these concepts I’ve stated may be ludicrous and seemingly unrealistic, there is always the chance for change and the unexpected. Maybe one day TB will be erased from the world and we will have yet another reason to celebrate the extinction of a terrible disease, but I ask, what other disease will take its place? TB has grown with humanity for so long, and as the period of time comes in which it may finally be defeated I merely pose the question to you, wouldn’t it have been miraculous to have gotten another ally to our immune system?

Tuberculosis has plagued humans for such a long time. It is responsible for millions of deaths for a very long time. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is the pathogen responsible for the onset of tuberculosis disease. It generally affects the lungs but can also affect any other organ in the body.

In order to contract TB one must breath air contaminated with Mtb. Once infected with Mtb, two outcomes are possible. You are either a carrier or you develop tuberculosis. Anyone with a compromised immune system is more likely to develop TB. Once you have active TB, you are able to spread it from person to person.

Treatment last anywhere from 6 months to 2 years depending on the strain you have contracted. If drug course not followed multi drug resistant TB can develop and if it continues beyond this, extensively drug resistant TB can develop increasing the drug course to a minimum of 2 years of treatment.

With this information you probably think that TB evolves a lot to become resistant to drugs of the 21century, but this is not the case. A person is usually infected with multiple strains at the same time and the majority of people already have lung issues to start with. TB is more of an opportunistic pathogen in that sense.