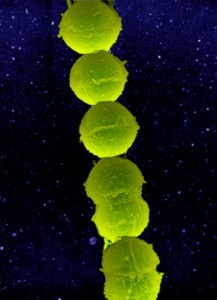

Preterm birth—the birth of an infant before 37 weeks of pregnancy—is the greatest contributor to infant death, and a leading cause of long-term neurological disabilities in children. One of the causes of preterm birth is Group B Streptocuccus (GBS) infection in pregnant women. GBS frequently colonizes the lower genital tract of healthy women without causing any symptoms. However, it may cause severe infections during pregnancy by ascending from the lower genital tract into the amniotic cavity. Infection of the amniotic fluid can lead to fetal injury.

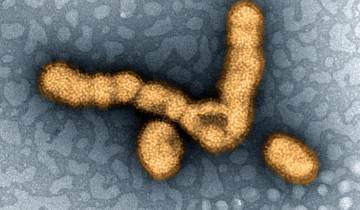

GSB is able to penetrate the human placenta with the help of a hemolytic pigment toxin, which consists of lipids. This toxin is a lipid that stains the bacteria orange/red and is able to induce not only hemolysis, or destruction of red blood cells, but also pyroptosis—a specific form of cell death—in macrophages, white blood cells that eliminate microscopic particles, such as bacteria and dead cells.

Now, results from a new study (Group B Streptococcus circumvents neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps during amniotic cavity invasion and preterm labor) published in the journal Science Immunology (October 14, 2016) show that the GBS pigment toxin damages neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps in placental membranes. The study was carried out using a pregnant nonhuman primate model that closely mimics pregnancy in humans and allows monitoring of uterine contractions, timing of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity, and immune responses during pregnancy-associated infections. Using this model, researchers could follow the course of GBS infection from the initial stages until preterm labor, a process that would be impossible to experimentally follow in humans.

The researchers found that increased production of the hemolytic pigment toxin enables GBS to penetrate the placental membranes and infect amniotic fluid and fetal organs as early as within 15 minutes to within a few hours after infection. The infectious process induced increased release of messenger proteins that specifically recruit neutrophils. However, despite the recruitment of neutrophils, GBS producing large amounts of the hemolytic pigment toxin were able to infect multiple fetal organs.

Neutrophils are white blood cells involved as a first line of defense in controlling the spread of infectious microbes, and kill these microbes using a process called phagocytosis—they engulf and then digest the microbes using an arsenal of powerful toxic substances. Therefore the neutrophil is one type of phagocytic cell, so-called after the Greek for “devouring cells”. Neutrophils use an additional strategy to entangle, immobilize and kill microbes—they extrude stringy DNA webs known as neutrophil extracellular traps. Large numbers of neutrophils reside in the bone marrow and circulate in the blood. At the beginning of an infection, the early inflammatory process results in the production of a specialized set of cytokines and chemokines, protein messenger that signal neutrophils to travel from the blood and bone marrow to the site of infection.

The researchers found that the hemolytic pigment toxin induced neutrophil cell death. Therefore, when the neutrophils reached the site of infection to kill GBS following cytokine and chemokine signals, they were killed themselves by the GBS hemolytic pigment toxin, which damaged the neutrophils’ cell membrane. Moreover, the toxin induced formation of neutrophil extracellular traps in the placental membranes. However, GBS that produced large amounts of the hemolytic pigment toxin could not be killed by the neutrophil extracellular traps, and were therefore able to invade the amniotic fluid.

Together, the study results show that the hemolytic pigment toxin enables GBS to avoid killing by neutrophils and their extracellular traps. In absence of killing by neutrophils, GBS is able to damage the placental membranes and induce both fetal injury and preterm labor. The study results also indicate that the GBS hemolytic pigment toxin could be a target for novel strategies developed to prevent GBS infection in pregnant women and subsequent damage to the fetus.

What really grabbed me about this article was the efficiency of GBS to infect the amniotic fluid and fetal organs in a matter of minutes to hours. Something so effective at avoiding host immune response and infecting so quickly combined with an organism that can be “frequently” found in women, I have to admit I’m surprised that this is the first I’m hearing about this issue. Granted, I’m a male, so perhaps that’s why. So how “frequently” is GBS actually found in women? According to the CDC, a whopping 25% of pregnant women actually carry GBS! With a number so high, my next question is, statistically, how much more risk is there for preterm birth associated with GBS? One study sought to answer this very question by examining nearly 1000 women, nearly 100 of whom were established as carrying GBS. The study ultimately concluded that pregnant women carrying GBS were over twice as likely to have premature labour, among other potential complications. With these kinds of eye-popping numbers, it’s clear why the CDC recommends that pregnant women be tested for GBS during pregnancy.

Citation: Prevention in Newborns. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/groupbstrep/about/prevention.html. Published 2016. Accessed November 9, 2016.

Citation: Allen U, Nimrod C, MacDonald N, Toye B, Stephens D, Marchessault V. Relationship between antenatal group B streptococcal vaginal colonization and premature labour. Paediatrics & Child Health. 1999;4(7):465-469.

Any type of infection during pregnancy can be tricky to deal with as the rules of placental transmission and swapping of mother and baby’s fluids during birth can provide an easy pathway for vertical transmission of the pathogen. Because GBS is asymptomatic in up to 30 percent of the women infected, a pregnancy screening for this bacteria can be the first time the expectant mother is aware she is infected. Luckily, intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis given during birth has an effectiveness of 86-89 percent in preventing transmission of GBS to the newborn. This seems like a simple enough solution, but unfortunately antibiotic resistance can be an issue. Therefore a vaccine would be the best method to prevent infection in the first place, though one has not yet been developed. It would make the most sense to put our efforts into development of a GBS vaccine to prevent these associated problems. However Group B Streptococcus is so prevalent in the environment and typically colonizes humans transiently, that it perhaps it would only be beneficial to those who are seeking to become pregnant and are not already infected with the bacteria.

Citation: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5910.pdf Published October 2010. Accessed November 9, 2016.

Due to the mother having to produce the require amounts of antibody it may be good for gynecologists and obstetricians to inform their female patients as soon to become vaccinated for GBS. A survey conducted for women regarding their willingness to take an antenatal vaccine after being informed about the effects that GBS would have on their infants was over 80% average from all of their asked groups, with those that rejected taking a vaccine doing so due to concerns of risks/safety or not believing in vaccines. This would indicate that once a vaccine becomes legally available in the U.S it would be a matter of gynecologists ( as a male I am sorry if I misunderstand the kind of conversation carried out with one’s gynecologist) and obstetricians informing women who are pregnant or planning on getting pregnant. An advantage that women who were planning to get pregnant over those already pregnant would be that they could take the vaccine with ample time for it to run it’s course on the body and produce the beneficial IgG long before it could pose any danger to the embryo.

citation: McQuaid, F., Jones, C., Stevens, Z., Plumb, J., Hughes, R., Bedford, H., … & Snape, M. D. (2016). Factors influencing women’s attitudes towards antenatal vaccines, group B Streptococcus and clinical trial participation in pregnancy: an online survey. BMJ open, 6(4), e010790.

@Ashley I completely agree with you. I believe that vaccine would be the best solution for GBS infection. A vaccine would significantly reduce the need for antibiotics in pregnant women during labor and in infants who contract a group B strep infection, which also means removing one more contribution to antibiotic resistance concerns and reducing one more need for antibiotics that can influence infants’ gut bacteria development.

There was a Phase 2 study conducted at University Hospital Antwerpen in Antwerp, Belgium where they found a vaccine covering three strains of group B strep(Ia, Ib and III) to be effective with no major safety concerns, though more studies with many more women are necessary before the study would undergo the process for FDA approval. In this study, research team randomly divided 86 women from Belgium and Canada into 51 women who received the vaccine and 35 women who received a placebo.

The researchers focused on how effectively the vaccine led mothers’ antibodies to transfer to their infants. About 66-79% of the women who received the vaccine transferred antibodies to their infants, and those antibody concentrations remained in the babies at a rate of 22-25% three months later. The antibody levels of the mothers themselves increased by 16 to 23 times, depending on the serotype, after vaccination.

Citation:

Donders, Gilbert G.G. MD, PhD; Halperin, Scott A. MD; Devlieger, Roland MD, PhD; Baker, Sherryl PhD; Forte, Pietro BA; Wittke, Frederick MD; Slobod, Karen S. MD; Dull, Peter M. MD Maternal Immunization With an Investigational Trivalent Group B Streptococcal Vaccine: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Obstetrics & Gynecology: February 2016 – Volume 127 – Issue 2 – p 213–221

This bacteria is something that researchers should be putting a lot of focus on since it is fast acting, difficult to diagnose and just as hard to treat and prevent. Especially with the knowledge of how this bacteria evades the immune system, this should help us develop preventative measures.

This month a group of researchers published a study on preventative measures to fight this bacteria. A soluble form of Siglec-9 provides a resistance against Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in transgenic mice is an investigation into the specific genes that aid in GBS binding to neutrophils. They found that a component of GBS called capsular polysaccharide (CPS) binds to Siglec-9 and this is what down-regulates the effects of neutrophils on the infection. From here they were able to create a soluble form, sSiglec-9, that can inhibit the binding of CPS through competition with the original form of Siglec-9. This gene therapy gave a line of treated mice the tools they needed to eliminate GBS. With this study being so new it’s hard to tell how relevant it would be to preventing preterm birth complications but I thought it was an interesting development.

Citation: Saito, M., Yamamoto, S., Ozaki, K., Tomioka, Y., Suyama, H., Morimatsu, M., Nishijima, K.-i., Yoshida, S.-i., Ono, E., 2016. A soluble form of Siglec-9 provides a resistance against Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in transgenic mice. Microbial

The utilization of competitive inhibition to neutralize the effect of the toxin seems like an innovative move by the researchers as it would make it harder for the bacteria to evolve a measure around the inhibitor without loosing efficiency. Treatment plans that would utilize a combination both, this drug and a vaccine ( that covers 3 strains of GBC and has finished phase 2 trials) , to functionally eliminate the spread of GCB with humans being their main reservoir .

C. Fischer,

The article you posted was inspiring. We now know that some research is being done to try and remedy the GBS problem 25% of pregnant women deal with. If the competitive inhibitor works in humans, then I think this could stop premature birth caused by GBS infection. I think the soluble sSiglec-9 would be a good treatment because it is not an antibiotic and we won’t have to worry about new antibiotic resistant GBS evolving.

After thinking about this kind of treatment, there are some drawbacks. One drawback is that GBS is not cleared or eliminated from the colon or vagina with this treatment. Thus, the second drawback is the question of whether the pregnant women would have to take the soluble sSiglec-9 for the duration of her pregnancy, similar to how she would take prenatal vitamins? I assume the answer to this question would be yes because if she stops taking the treatment, GBS would inhabit the amniotic cavity. This leads me to another drawback. Would taking the treatment reverse infection or just prevent it? This is an important question because carriers of GBS deliver their babies to full term without intervention. They are not infectious. However, this is not true for pregnant women infected with GBS. So, in other words, does this mean if your infected with GBS already the treatment won’t help/work? Another inquiry is the impact the soluble sSiglec-9 has on the fetus. I doubt that it would harm the fetus because the treatment would be an inhibitor of GBS binding. Nonetheless, I appreciate how the researchers found some way to block GBS.

After reading the Group B Streptococcus (GBS) and pregnancy article, I was shocked to learn 1 in 4 or 25% of pregnant women are carriers of GBS. The literature provides some relief by disclosing that not all carriers are infected. Carriers don’t become sick and there is no risk to your health as a carrier. Also, no treatment is available for a carrier. GBS is commensal microbiota of the colon and vagina. Commensal microbiota are resident micro-organisms that cover the surfaces of the human body. The skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract are a few environments where non-harmful bacteria reside. These bacteria evolve with the host and offer protection. If an invader or foreign microorganism joins the community, their growth is inhibited because the resident microbes consume all the resources and usually the resources available only support the resident microbiota.

I believe GBS sees a window of opportunity as the fetus begins to develop. There are several changes in the microbiota of the uterus and new cells are formed as the placenta matures. These changes may induce GBS infection.

More on commensal bacteria can be found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15158604

This is a very interesting study about GBS infection and its colonization and its impact during pregnancy. It is very sad that the fetal organs get infected with GBS and may also lead to death soon after the birth. GBS is a complex issue, it is not very evident that the current treatment pattern is fully flourished and get the best way to eliminate the worst impact. It also has potential dangers in and of itself. There are antibiotic resistant GBS and treating them with antibiotics may lead to kill the normal flora and make the situation worst.and some mothers are allergic to antibiotic may lead to anaphylaxis Both of these factors make it important for consider how to avoid the infection as such during the pregnancy in natural and healthy way.

It is always important and beneficial for all the pregnant mothers to build a healthy routine and healthy [intake of food into their lifestyle to foster healthy microbiota](https://www.naturalbirthandbabycare.com/prevent-group-b-strep), and to focus particularly on good flora in the vagina at the end of pregnancy. This not only helps build lifelong health for them , but it also keeps the baby healthy gut flora from the start – and it’s most likely far better treatment for GBS than the antibiotic treatments .

citation:

Outbreak of Late-onset Group B Streptococcal Infections in Healthy Newborn Infants after Discharge from a Maternity Hospital: A Case ReportJ Korean Med Sci. 2006 Apr; 21(2): 347–350.

Published online 2006 Apr 20. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.2.347

I completely agree with you on the potential hazards of overusing antibiotics to manage these types of situations. While it seems appropriate to start blanket antibiotic therapy on all neonates to protect them from the potential GBS meningitis or sepsis, it could be causing unintended harm to the neonate in ways not immediately considered. For instance, in a 2012 study by Fouhy et al. found that newborns who received IV antibiotic therapy within 48 hours of birth had a lower level of beneficial gut microbes, at 4 and 8 weeks after antibiotic administration, than those newborns who did not receive antibiotics. (Fiona Fouhy, Caitriona M. Guinane, […], and Paul D. Cotter. High-Throughput Sequencing Reveals the Incomplete, Short-Term Recovery of Infant Gut Microbiota following Parenteral Antibiotic Treatment with Ampicillin and Gentamicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Nov; 56(11). This highlights the fact that antibiotic administration should not occur nondescriminately in all birth situations, but should be taken on a case by case basis. Both the mother’s and baby’s risk factors for potential infection should be taken into account when deciding to give antibiotics. If an active GBS infection is present during or leading up to birth then it is likely more beneficial to provide the antibiotic therapy to the newborn since the risk for infection is high, even if the effect on gut microbiota is negative. It comes down to a cost versus benefit analysis that the clinician must complete to make the best decision for both baby and mother.

I was very surprised to know how the infection with GBS in mother can infect the fetus in such a short time. I admit that this is for the first time I am hearing any infectious agent being so fast. Though above post has given a great detail of information about the GBS, it says a little about the effect of GBS on fetus. So, I tried to delve deeper into this aspect. Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a type of gram-positive streptococcal bacteria, also known as Streptococcus agalactiae. GBS is commonly found in adults and older children, and usually does not cause infection. There are two ways in which it may be passed on to a newborn baby. The infant can become infected as the baby passes through the birth canal. In this case, babies become ill between birth and 6 days of life (most often in the first 24 hours). This is called early-onset GBS disease. The infant may also become infected after delivery by coming into contact with people who carry the GBS infection. In this case symptoms appear later, when the baby is 7 days to 3 months or more old. This is called late-onset GBS disease. Most babies who become infected can be treated successfully with IV antibiotics and can make a full recovery. However, infection can sometimes cause life-threatening complications, such as: blood poisoning (septicemia), infection of the lung (pneumonia), and infection of the lining of the brain (meningitis). According to CDC, in the United States, GBS is the leading cause of meningitis and sepsis in a newborn’s first week of life. GBS bacteria can rarely cause meningitis in adults. There are some factors that can increase an infant’s risk for group B streptococcal infection such as being born more than 3 weeks before the due date, especially if the mother goes into labor early, mother who has already given birth to a baby with GBS sepsis, and rupture of placental membranes more than 18 hours before the baby is delivered. Presence of GBS bacteria in a blood sample from infected newborn is considered to be a positive diagnostic test.

This article was very interesting to me. Group B Streptococcus (GBS) can cause significant maternal and neonatal morbidity. Group B Strep is a commensal bacterium that can live in the human host without being helpful or harmful. Colonizing in the GI tract, vagina, or urethra it can cause urinary tract infections, compromising the neonate who can develop an infection during or following birth. This article left me wondering how many fetuses make it to full-term and lead healthy lives if affected with GBS. According to research, the GBS bacteria is found in about 25% of all healthy adult and pregnant women. In the UK, where this is prevalent, 300-400 infants develop early-onset group B streptococcal disease every year with 40 of them being fatal. 99.85% of infants born to mothers with GBS will not be affected by death or disability. A precautionary screening is preferred to determine risks for GBS.

Citations

Ahmadzia H, Heine R. Diagnosis and Management of Group B Streptococcus in Pregnancy. Obstetrics And Gynecology Clinics Of North America [serial online]. December 1, 2014;41(Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy):629-647. Available from: ScienceDirect, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 12, 2016.

Beacock M. Newborn examination on full-term neonate whose mother had group B streptococcus colonisation. British Journal Of Midwifery [serial online]. September 2016;24(9):643-649. Available from: Consumer Health Complete – EBSCOhost, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 12, 2016.

According to World Health Organization(WHO), prematurity is the leading cause of death in children under the age of 5 across the globe. More than 60% of preterm births occur in Africa and South Asia. It is estimated that preterm birth affects about 1 of every 10 infants born. The infant mortality rate among African American infants is 2.4 times higher than that of White infants, primarily due to preterm birth. In the United States, the risk of preterm birth for Non-Hispanic black women is approximately 1.5 times the rate seen in white women. Though Group B Streptococcus (GBS) was found in humans in 1938 it wasn’t until the 1970s that it was linked to preterm birth. The CDC suggests that 1 in 4 women carries GBS and the disease rates are higher among infants born to African-Americans of all age groups.

This was an interesting correlation that shows that African American women are at a higher risk for preterm births and GBS. This leads to the question what are the possible reasons for this occurrence. According to a study there are several factors were associated with GBS including the number of deliveries occurring among women who had received no prenatal care, were on medical assistance, low birthweight babies, as well as the number of deliveries in African American patient. Hospitals with more African American obstetric patients and more obstetric patients lacking prenatal care had more GBS disease, while hospitals with GBS screening policies had significantly less disease. The disparity of GBS amongst African Americans is due mainly in part to lack of access to proper healthcare. Since the late 1990s there has been a 75% decrease in the disparity between blacks and whites with GBS due to early testing of mothers. Testing for GBS has significantly improved the survival rate of infants and decreased the gap.

Citation:

1.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs363/en/

2.https://www.cdc.gov/media/subtopic/matte/pdf/cdcmattereleaseinfantmortality.pdf

3.http://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/entertainmented/tips/strep.html

4.Schuchat, A. (1998). Epidemiology of Group B Streptococcal Disease in the United States: Shifting Paradigms. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 11(3), 497–513. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC88893/

5.http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/33/6/751.full.pdf

A vaccine for GBS recently finished phase II clinical trials. The results are promising – http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Citation/2016/02000/Maternal_Immunization_With_an_Investigational.5.aspx – though one case of neonatal asphyxia was found to be potentially due to the vaccine. Interestingly the paper found that timing of administration had no demonstrable effect on effectiveness so potentially it could be administered in early adolescence with a booster later in adolescence or early in the pregnancy. This could allow the risk of seriously adverse side effects to be minimized.

The Group B Streptococcal infection can cause threat to the woman because 25% of all woman are infected with GBS .1 in 200 babies of infected mothers are become ill. Eventhough the person is responsive to the antibiotic, Treating the mother with oral antibiotics during the pregnancy cannot completely eliminate the bacteria from her sysytem and make the baby protected. During the vaginal birth , the baby get exposed to the bacteria and if we are trying to treat treat the baby with antibiotics after birth is often too late to prevent illness if the baby is at high risk for contracting GBS. Intravenous antibiotics are recommended during delivery to reduce the chance of your baby becoming sick. It is recommended that antibiotics are given once labor has begun and every four hours during active labor until the baby is delivered.

Williams Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://www.cdc.gov March of Dimes, http://www.marchofdimes.com

This is interesting, I had no idea that there was a bacterial infection that is present in such a large number of women and has such negative impact on the fetus. I agree with C. Fischer that something needs to be done and I’m glad that there are already measures taken with promising results showing nearly a 57% increase in the survival rate for mice infected with GBS who received treatment in comparison to those who did not. If clinical trials go well this could potentially be a strong first step against a prevalent bacterial infectious agent.

C. Fischer’s citation:

Saito, M., Yamamoto, S., Ozaki, K., Tomioka, Y., Suyama, H., Morimatsu, M., Nishijima, K.-i., Yoshida, S.-i., Ono, E., 2016. A soluble form of Siglec-9 provides a resistance against Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in transgenic mice. Microbial

After reading the article, the ultimately solution to this issue is the elimination of the bacteria from our normal flora all together. As expressed before, our normal flora provides us with many benefits such as: a manipulated pH environment that inhibits the growth of harmful bacteria and also covers the surface of the gastrointestinal tract and skin to prevent colonization of those bacteria, but a bacteria of the normal flora by the name of Group B streptococcus (GBS) has been found to produce a pigment toxin that causes pre-term births and fetal injury, and because it is proven to be harmless to most people (1), its removal should have no adverse effects. GBS can be eliminated from the body through use of ampicillin (3), an antibiotic therapy that attacks the bacteria’s cell structure and causes osmotic lysis. If the bacteria is removed prior to pregnancy, there would be no need to administer antibiotics during the term, which on its own has been proven to cause asthma in the fetus later on in life due to the use of antibiotic taken in the third semester (2). This is usually the time that pregnant women will be tested for GBS according to the CDC (4). A new approach should be taken to eradicate Group B Streptococcus prior to pregnancy and thus move our focus from treatment to prevention.

Citation:

1. Mayo Clinic Staff. Group B strep disease. Mayo clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/group-b-strep/home/ovc-20200548. Accessed November 13, 2016.

2. Stensballe L, Simonsen J, Jensen S, Bønnelykke K, Bisgaard H. Original Article: Use of Antibiotics during Pregnancy Increases the Risk of Asthma in Early Childhood. The Journal Of Pediatrics [serial online]. April 1, 2013;162:832-838.e3. Available from: ScienceDirect, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 13, 2016.

3. Woods, Christian J., Streptococcus Group B Infections Treatment & Management. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/229091-treatment. Published October 24, 2016. Accessed 13 November, 2016.

4. Prevention in Newborns. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/groupbstrep/about/prevention.html. Published May 23, 2016. Accessed November 13, 2016.