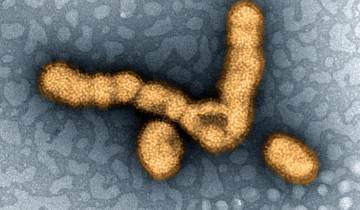

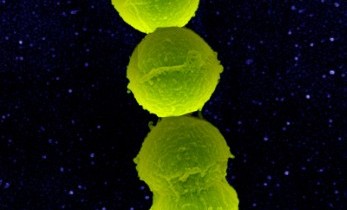

“Both inside and out, our bodies harbour a huge array of micro-organisms. While bacteria are the biggest players, we also host single-celled organisms known as archaea, as well as fungi, viruses and other microbes – including viruses that attack bacteria. Together these are dubbed the human microbiota. Your body’s microbiome is all the genes your microbiota contains, however colloquially the two terms are often used interchangeably.”

Microbe colonization starts early during human development. “The fetus does not reside in a sterile intrauterine environment and is exposed to commensal bacteria from the maternal gut/blood stream which crosses the placenta and enters the amniotic fluid. This intestinal exposure to colonizing bacteria continues at birth and during the first year of life and has a profound influence on lifelong health. Why is this important? Intestinal crosstalk with colonizing bacteria in the developing intestine affects the infant’s adaptation to extrauterine life (immune homeostasis) and provides protection against disease expression (allergy, autoimmune disease, obesity, etc.) later in life. Colonizing intestinal bacteria are critical to the normal development of host defense.”

Although some scientists doubt that microbial colonization starts during intrauterine life, it is commonly accepted that an extensive exposure to microbial communities of fecal, vaginal, skin and environmental origins occurs at birth, and that this event has a major impact on the colonization of the neonatal gut.

Research findings show that during a natural vaginal birth, specific bacteria from the mother’s gut are passed on to the baby and stimulate the baby’s immune responses. However, this transmission is impacted in children born by caesarean section. The study (Birth mode is associated with earliest strain-conferred gut microbiome functions and immunostimulatory potential) has been published in the scientific journal Nature Communications on November 30, 2018.

Paul Wilmes, senior author of the study, said in a press release: “We find specific bacterial substances that stimulate the immune system in vaginally born babies. In contrast, the immune stimulation in caesarean children is much lower either because the bacterial triggers are present at much lower levels or other bacterial substances hamper these initial immune reactions to happen.”

For the study, the researchers analyzed the structure and function of gut microbial communities in newborn babies and their mothers using metagenomic analysis—and comparing neonates delivered vaginally with those delivered through cesarean section. The study results show differences between the microbiomes of the vaginally delivered neonates and the microbiomes of the neonates delivered through cesarean section. The researchers found that in vaginally delivered babies several functional pathways are over-represented as compared to the neonates delivered through cesarean section. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis is one of the over-represented functional pathways, and this over-representation appears to be the result of specific bacterial strains that are transmitted from mothers to neonates during vaginal delivery.

The researchers stimulated primary human immune cells with LPS isolated from early stool neonatal samples, and found higher levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) and interleukin 18 (IL-18) production in cells stimulated with stool samples from vaginally delivered neonates as compared to cells stimulated with stool samples from neonates delivered through cesarean section. Accordingly, the researchers observed higher levels of TNF-α and IL-18 in neonatal blood plasma from vaginally delivered babies.

The researchers conclude that cesarean section delivery disrupts mother-to-neonate transmission of specific microbial strains, thus affecting immune stimulation during a critical window for the priming of the neonatal immune system.

Currently, there are several studies that have correlated the association of maternal microbiota with the microbiota of infants born through vaginal birth. In another interesting find, one study determined that vertical transmission of Actinobacteria and Bacteroidia occurred in vaginally born infants and not in caesarean born infants. The transmission of bacteria was confirmed through fecal metagenomics analysis using rare marker single nucleotide variants. These classes of bacteria are associated with a controlled selection of microbiota which establishes a stable community in the infant after being transmitted from the mother during birth. The study attributed the selection of Actinobacteria and Bacteroidia to their ability to inoculate into the infant through maternal fecal matter and their ability to withstand a milk based diet. It was also speculated that colonization of these microbiota are responsible for preventing environmental bacterial growth in the infants by competing for resources. Infants born through caesarean section were determined to not have maternal strains of Actinobacteria and Bacteroidia; they experienced a high flux in the types of bacterial strains found when compared to vaginally born infants. It was also determined that as the infant passes the age of one, the similarity between the maternal microbiome and child’s microbiome becomes more dissimilar because the child’s microbiota is influenced by the environment and a change in diet. Although, the differences in microbial activity in vaginally born infants compared to caesaren section born infants is distinct, the researchers determined that the method to which the infant’s developing immune system is disrupted is unknown. It would be interesting for future studies to determine how exposure to or the lack of exposure to maternal microbiota as an infant influences the immune system long term.

Reference:

Korpela, K., Costea, P., Coelho, L. P., Kandels-Lewis, S., Willemsen, G., Boomsma, D. I., Segata, N., & Bork, P. (2018). Selective maternal seeding and environment shape the human gut microbiome. Genome research, 28(4), 561–568. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.233940.117

Those who are born vaginally have similar bacteria as the mother’s vagina, while those who are born via c-section have bacteria found on the skin. I heard that there’s a practice called vaginal seeding where babies born by c-section are swiped all over the body by gauze place in the vagina to give them some of the bacteria. There have not been many trials to see its efficacy but its a cheap and easy procedure to do to introduce some vaginal bacteria to minimize the chance of diseases seen in those birth through C-section. As for other factors that make the infant microbiome distinct from the mother’s please refer to my comment on the same post where I talk about factors that can influence the microbiome in early childhood

Reference:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26906151

Noting your statement of how the similarities between an infant and its mother’s microbiome began to diverge with time, I’d like to focus as to why selective maternal seeding should be approach with caution. The distinct difference found between those birthed naturally and those birthed by cesarean are obtained due a difference of biomes for simply a matter of several minutes. It is not an invasive procedure but yet, yields such a world of a difference according to some studies. What would happen if something were to go wrong?

Until long term effects can be determined, I feel as though we should refrain from doing this as a means of improving a newborn’s immune system. They are extremely sensitive to their environment, and the supposed beneficial outcome of vaginal seeding in the long run is theoretical at the moment to say the least. It has, however, been well studied and proven that there is a possibility for the presence of harmful microbes in the birth canal which can and has affected many newborns, in some cases, even proven to be fatal. Taking this and directly applying it to the baby seems to me, to result in a more definite outcome which may be good, but in the presence of a harmful microbe, this may ensure definite fatality.

Contrasting from the studies presented in the post, I researched upon how birth mode translated into the bacterial communities of a newborns meconium, the placenta, and fetal membrane. This study presented that the newborns from contrasting birth modes had comparable microbial communities. If this is the case, it turns out that you may be exposing a newborn to unrequited, pointless risk.

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6945248/

The blog post, “The Immune Response: Birth Mode and microbiome.” was a very informative article focusing on the birth response to the microbiome. By reading the blog post, it intrigued me to ask the following question: does breastfeeding have an impact on a baby’s microbiome? By doing research, I was able to find a scientific paper called “Meta-analysis of effects of exclusive breastfeeding on infant gut microbiota across populations.” This article focusses on how exclusively breastfed and non-breastfed babies can have an impact on a baby’s microbiome. The scientists were able to do the study by analyzing both exclusively breastfed and non-breastfed babies’ stool samples to compare the gut microbiota (1825 stool samples from 684 infants). Analyzing the data from both exclusively breastfed and non-breastfed babies stool samples indicated that breastfed babies have a significantly lower amount of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes in their microbiota.

References

Ho, Nhan T, et al. “Meta-Analysis of Effects of Exclusive Breastfeeding on Infant Gut Microbiota across Populations.” Nature Communications, Nature Publishing Group UK, 9 Oct. 2018, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6177445/.

I also have to admit that I was not aware that a Cesarean birth could influence an infant’s immune system. Upon reading your comment, I learned that lactobacillus was abundant in the flora of normal women, but not in those who have endometriosis. I wondered if this situation only applied to healthy women, and those with endometriosis. After conducting research, I came across the article, Cesarean versus Vaginal Delivery: Long term infant outcomes and the Hygiene Hypothesis, published in June 2011. In this article, there was a study that studied the body’s colonization of microbes. Babies that were born vaginally had mostly colonization of Lactobacillus, however babies that were born cesarean did not. Cesarean babies were colonized by mostly skin flora such as Staphylococcus and Acinetobacter. This difference in microbiota due to mode of delivery and transmission greatly impacts the infants’ immune system abilities, and supports the overall message of the blogpost.

Reference:

Neu, J., & Rushing, J. (2011). Cesarean versus vaginal delivery: long-term infant outcomes and the hygiene hypothesis. Clinics in perinatology, 38(2), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2011.03.008

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3110651/

I believe that mothers should be knowledgeable about the importance of exposure to the vagina microbiome for infants because it influences a child’s immune system. Before reading this, I knew that bacterial colonies around the body differed in size and types of bacteria. However, I did not know that infants born via cesarean section had an impacted transmission that affects what bacteria they come in contact with and can result in them not coming in contact with the bacteria that stimulates their immune responses. This made me wonder if reproductive disorders in mothers alter the vaginal microbiome in a way that would affect an infant’s immune response. Upon my research, I found that women with endometriosis showed a difference in flora along the reproductive tract. In normal women, the balance of flora is stable throughout the reproductive tract, and lactobacillus is most abundant. However, in women with endometriosis, lactobacillus was dramatically decreased in the upper reproductive tract, and flora overall was more diverse. Lactobacillus is a bacteria that can stimulate the immune system. Therefore, it seems that babies born vaginally to mothers with endometriosis don’t get the same exposure to immune response stimulating bacteria as an infant born to a healthy mother.

References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32299442

EN, this is a very interesting topic, I’ve personally never heard of “vaginal seeding.” After researching the topic, a-little more, I learned that this topic has created a lot of debate. There are many who believe that exposing babies born by caesarean mode, to the mother’s vaginal microbiota would be beneficial and there are many who believe that it wouldn’t make much of a difference. A researcher, Stinson, has made the argument that it may not be the exposure to the mother’s vaginal microbiota that protects children from immune disorders in the first place but rather the hormonal triggers at the onset of labor. If this were the case, vaginal seeding would only introduce the baby to additional bacteria, for no good reason. Also noted were the risks of vaginal seeding such as reported cases of neonatal herpes simplex infection. I feel that these risks could be ruled out with simple blood tests of the mother before the seeding attempt, therefore, I am pro vaginal seeding, as there have been many studies that positively link caesarean section birth mode to autoimmune conditions.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6599328/

I believe that mothers should be knowledgeable about the importance of exposure to the vagina microbiome for infants because it influences a child’s immune system. Before reading this, I knew that bacterial colonies around the body differed in size and types of bacteria. However, I did not know that infants born via cesarean section had an impacted transmission that affects what bacteria they come in contact with and can result in them not coming in contact with the bacteria that stimulates their immune responses. This made me wonder if reproductive disorders in mothers alter the vaginal microbiome in a way that would affect an infant’s immune response. Upon my research, I found that women with endometriosis showed a difference in flora along the reproductive tract. In normal women, the balance of flora is stable throughout the reproductive tract, and lactobacillus is most abundant. However, in women with endometriosis, lactobacillus was dramatically decreased in the upper reproductive tract, and flora overall was more diverse. Lactobacillus is a bacteria that can stimulate the immune system. Therefore, it seems that babies born vaginally to mothers with endometriosis don’t get the same exposure to immune response stimulating bacteria as an infant born to a healthy mother.

References:

Wei, Weixia, et al. “Microbiota Composition and Distribution along the Female Reproductive Tract of Women with Endometriosis.” Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 16 Apr. 2020, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32299442.

Hi BJH,

While reading the original blog post, I was also thinking of possible disorders that would affect a mother’s microbiome! So, it was interesting to read your comments about the effects of endometriosis on a mother’s flora in comparison to mothers that do not have endometriosis. I did some further research on other disorders that could possibly have an effect on a mother’s microbiome, and I found an article on HIV and its relationship with the microbiota of a mother and an infant’s. This paper was interesting because the results from the study show that mothers with or without HIV infection did not have a large difference in the make up of their vaginal microbiota. However, there is a correlation between maternal HIV infection and the microbiome of HIV-exposed, uninfected infants. In addition to differences in vaginal microbiota, different levels of human breast milk oligosaccharides from mothers infected with or without HIV were found and associated with bacterial species in the infant microbiome. Due to maternal HIV infection, there seems to be a disruption within the expected microbiome of an infant. This association could possibly contribute to increased morbidity and mortality rates of HIV-exposed, uninfected infants.

Article: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27464748

Bender, J. M., Li, F., Martelly, S., Byrt, E., Rouzier, V., Leo, M., Tobin, N., Pannaraj, P. S., Adisetiyo, H., Rollie, A., Santiskulvong, C., Wang, S., Autran, C., Bode, L., Fitzgerald, D., Kuhn, L., & Aldrovandi, G. M. (2016). Maternal HIV infection influences the microbiome of HIV-uninfected infants. Science translational medicine, 8(349), 349ra100. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf5103

Thank you BJH for sharing how women with endometriosis have decreased number of lactobacillus in the upper reproductive tract. While I was reading through your comment, I was more interested in what lactobacillus do and why it promotes good immune system. Upon research, there were different mechanisms how lactobacilli maintain homeostasis environment in woman’s vagina. One of the major roles of lactobacilli was their ability to make use of glycogen breakdown products in the human vagina to produce lactic acid. The production of lactic acid was very important because it inhibits to growth of other bacteria by acidification of the environment in the vagina to pH level of 3.0-4.5. Also, lactobacilli are bound to vaginal epithelial cells and it prevents from other microorganism attaching and infecting the vaginal epithelial cells. Nonetheless, lactobacilli produced bacteriocins which kills other bacteria. It was very interesting to learn the importance of lactobacilli for their anti-microbial activity and also correlate how this can promote maternal health and proper fetal development.

Reference:

Witkin, SS, Linhares, IM. (2017). Why do lactobacilli dominate the human vaginal microbiota? BJOG., 124: 606– 611. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14390

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28224747

While reading the article, I wonder if there are any other factors other than the mode of birth that could benefit the neonate microbiome. In my research, I found research done by Tamburini et al. looking at how early life microbiome will affect health outcomes. In this article, the researchers listed some other factors that could have an implication on the neonate’s microbiome. These include antibiotics, diet, probiotic supplements, environmental exposures, and host genes. It has been shown that the constant use and even low dosage use of antibiotics in early life can disrupt the gut microbiome and lead to an increased risk of many conditions, such as type 2 diabetes. As for diet, breastfeeding has been shown to reduce health risk for neonates in the future because breast milk contains not only beneficial microbes but also IgA and other proteins. As for probiotic supplements, there are researches done that show that they can be helpful. Common probiotics include lactobacillus and bifidobacterium, which are the most abundant types of bacteria found in the gut. Another factor that can influence early life microbiome is environmental exposures; cohabitation increases the probability of bacterial exchange, and exchanges can lead to life long colonization. Exposure to pets also increases immune tolerance and reducing the risk of allergies and asthma in neonates. The last factor listed was the host genome. Further studies are needed to see how the host genes interact with the microbiome composition.

The immune system and the microbiome are necessary for homeostatic response to infections. Neonate’s immune system are initially exposed to microbes during vaginal birth. The immune system is biased towards T helper 2 cells and are against T helper 1 cells, which allows microbes to colonize but make them more susceptible to infections.

Reference:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27387886

It has been confirmed through multiple studies that colonization patterns are different in individuals who undergo vaginal birth versus individuals that are brought out through caesarean section. With vaginal births you get a direct coating of bacteria from the mother in the birthing canal which stimulates the immune system faster in this group of individuals. However, this article negates the timeline of colonization between the two groups. Yes, individuals who are born vaginally have significant differences in colonization and diversity of organisms, but this only last within the first three months of infants of life. After about six months, this discrepancy between colonization rates in the two groups disappear and the group who have undergone cesarean sections are caught up to speed in their human microbiota diversity. So essentially, the first three to six month window is the vulnerable time in individuals who have been brought out through c-section, after this time both colonization rates are nearly equal. (158).

Rutayisire, E., Huang, K., Liu, Y., & Tao, F. (2016). The mode of delivery affects the diversity and colonization pattern of the gut microbiota during the first year of infants’ life: a systematic review. BMC gastroenterology, 16(1), 86

Hi Terry, I found your comment to be the most interesting out of the other comments due to its different viewpoint. Yes, there are clearly immense benefits in the immune system of the child through vaginal birth than that of a cesarean section, but your comment introduce the fact that after a certain point in a child’s life and the external exposure to various amounts of microorganisms, bacteria, and a multitude of organisms (i.e people), the colonization of bacteria is more than equal. Your comment gauged the question of, is there a way/method provided from the mother to increases the rate of microbiota colonization during this vulnerable time? Though there is no current evidence as to how scientist or mothers could build up their child’s immune system. This article from sciencedaily.com have found women wanting “vaginal seeding” to aid in the development of a child’s microbiome, due to its lack of evidence and concern of potential dangerous, this is not a viable option either. It’ll be interesting to see what the future holds, and the potential of this question ever being answered. Imperial College London. “Increased demand for ‘vaginal seeding’ from new parents, despite lack of evidence.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 24 February 2016. .

The idea that newborn babies that are vaginally born receive microbes that other babies born via cesarean delivery (C-section) are not able to receive is something that I have previously learned. This is one of the various reasons why medical professionals aim to use cesarean procedures only when needed because the mode of delivery is critical in an infant’s life. The article, “The Preterm Gut Microbiota: An Inconspicuous Challenge in Nutritional Neonatal Care,” further explains that preterm infants are usually born via C-section, resulting in health consequences that can have both short-term and long-term effects on their gut microbiota. The lack of diversity within their gut microbiota can cause preterm infants to be more prone to various infections and long-term consequences such as asthma and obesity. The study also explains that recent studies have incorporated the use of transferring vaginal bacteria from the mothers to their cesarean delivered infants in an attempt to alleviate the consequences of not being delivered vaginally. These studies have found that the vaginal transfer, also known as vaginal seeding, was partially able to restore the infant’s gut, oral, and skin microbiota. I find this very interesting and hope that further studies are better able to restore these cesarean-delivered infants’ microbiotas, which will ultimately facilitate the health and development of these infants.

Reference: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31001489

This is a great comment, and I had a similar question of some kind of doctor-mediated introduction of microbiota. Prior to reading your comment though, I had not heard of vaginal seeding. Interested, I did some research on it and I found some things that say that the long term effects of it are still not entirely known. And some researchers have stated that it could potentially be dangerous. But the problem of having a maladapted microbiome remains. I was able to find a paper discussing an alternative method of introducing B. infantis as it is more likely to take hold and adapt in the infant’s normal flora, and has a potentially stronger effect.

https://academic.oup.com/femsle/article/367/6/fnaa032/5739918

There have been many studies on the two modes of childbirth to determine which is most beneficial or most harmful. The most consistent knowledge is that a vaginal birth provides more benefits to a baby than a cesarean section. The data suggests that children born by-way of vaginal birth have a lower risk of communicable diseases, asthma, allergies, autoimmune disorders, and obesity. This is believed to be a result of a sort of “bacterial baptism,” in which the baby undergoes at the time of passing through the birth canal to exit the vagina. The mother’s body is home to a very extensive array of bacteria therefore, this level of exposure is likely to set a strong foundation in which the baby’s own microbiota can flourish. Babies born by Cesarean, aren’t exposed to this array of bacteria. The lack of bacterial exposure could be a cause for the lack of development in their immunological function, causing an increase in several chronic immune diseases. Not only has vaginal birth been deemed more beneficial over cesarean birth, but cesarean deliveries have also been noted to be directly harmful in some instances. This mode of delivery has been considered a risk factor for necrotizing enterocolitis in pre-term infants, with 64-80% cases being in babies of resulting Cesarean deliveries. It is understandable why cesarean deliveries are usually only recommended in the event that either the baby or the mother’s life could be lost during a vaginal delivery.

Reference

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5945806/

Hello Tiffaney Davis,

While reading your post concentrated on infant’s benefits about how vaginal birth babies have lower risk of asthma, allergies, autoimmune disorder and obesity, I was curious about the effects on the mother. I found an article called “Short-term and long term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and child” and this study showed that mothers who had c-section have higher risk of uterine rupture, abnormal placentation, hysterectomy, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, and preterm birth. Moreover, studies have shown that women without c-section displayed the risk of one event in 25,000 pregnancies for hysterectomy but women with one previous c-section displayed one event in 500 pregnancies. Further, the study showed risk of mother’s death during birth is higher in pregnancies after a c-section. Not only c-section has negative effects on the newborn child, it also shows great side effects on the mother as also. Due to these circumstances, I do agree with your thought on how c-section should be only recommended when baby or the mother’s life is at risk.

Reference

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30322585

Sandall, J., Tribe, R., Avery, L., Mola, G., Visser, G., Homer, C., . . . Temmerman, M. (2018). Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. The Lancet., 392(10155), 1349-1357.

Hi Tiffaney Davis,

I enjoyed reading your comment, it does a great job of establishing which mode of delivery is most beneficial and why. You mentioned that the lack of bacterial exposure to babies born via a C-section diminishes their immunological development and increases the risk of chronic immune disease. I decided to do more research on finding out more about which specific diseases they are at risk for and I found this article: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5591430/ that discusses that a delay in establishing a gut microbiome during the critical period of development leads to certain metabolic and inflammatory disorders such as obesity, asthma, type 1 diabetes, and food allergy in infancy. But a more pressing issue that was discussed in this paper was the increasing rate of C-sections performed. You mentioned that it is understandable why C-sections have to be performed under certain situations and The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that a C-section should only be done if the health of the mother and or baby is threatened and that C-sections should not exceed 10%-15% of the total deliveries. But in the past few decades, the number of C-sections has increased, especially in wealthier countries. This paper looked specifically at Latin American countries and found that more than half of the deliveries are C-sections! But why? The reason behind why is because it is more expensive than a vaginal birth and therefore makes more money. And because of this, it is done more frequently, especially in the private sector where there is less oversight. Despite the established correlation between mode of birth, the natural microbiome, and the overall health of the baby, it seems as though some medical establishments value money more. This is a quite surprising discovery considering the WHO has an established percentage, for good reason too, but people are still able to disregard this. I think given all this evidence of how C-sections affect the maturation of the immune system of these babies during a critical window, we should pass legislation and increase regulation of what is practiced in medical settings to reduce the number of unnecessary C-sections.

Good evening Tiffaney! I want to start by saying I enjoyed reading post on the benefits of vaginal birth. Your post was very informative. For example, I had no idea that vaginal births have so many benefits for the baby, such as lowering the risk of asthma, autoimmune disorders, and obesity. Reading your post, I now understand how vaginal birth is beneficial to the baby and gave me the question to research is a vaginal or cesarean section more useful overall. After a significant amount of research, I found an article called “Planned Caesarean Section Versus Planned Vaginal Birth for Breech Presentation at Term: A Randomised Multicentre Trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group” in this article, scientists studied different pregnancies at 121 centers in 26 countries. There were 2083 women selected for the study. 1041 women were assigned a planned cesarean section, and the remaining 1042 women had assigned planned vaginal birth. The data conducted from their research showed that women who had the planned cesarean section had a significantly lower risk of Perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality, or severe neonatal morbidity for their infants.

Reference

Hannah ME;Hannah WJ;Hewson SA;Hodnett ED;Saigal S;Willan AR; “Planned Caesarean Section Versus Planned Vaginal Birth for Breech Presentation at Term: A Randomised Multicentre Trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group.” Lancet (London, England), U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11052579/.

Immediately after reading this, not only was I a little taken aback by the new information I learned here about how mode of birth affects infants microbiota but, I was intrigued by what I found while reading my article reference as it had some differing points compared to this blog post. In the article, they conducted an experiment with pregnant women in their third trimester and collected samples of stool, oral gingiva, skin and vagina from each mother infant right at delivery. They then did some 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis and found that the neonatal microbiota and its functional pathways were pretty homogenous across all body sites at the time of delivery. By six weeks however, the microbiota of the infants had significantly expanded and diversified in terms of structure and function with the body site serving as the primary determinant of the composition and functional capacity. Granted that there were some minor variations in the neonatal microbiota community structure for C-sections, immediately at birth, after the six-week period, there was no observable difference in the microbiota community function between live birth and C-sections. They concluded from their research that in the span of six weeks in an infant’s life, the microbiota faces notable reorganization that is in fact driven by body site and not by the mode of delivery.

Reference:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5345907/

Hey Chelsea! I foung your comment interesting, and would like to thank you for the article as it contributes to further understanding this topic, as I was also surprised by the information. I always understood a microbiome to be introduction to building an immune response, however, the maturation of the immune system was what brought immune strength into light. It also makes me wonder whether the “reorganization” of microbiomes is something that is consistent with most healthy humans. I found an article: https://www.nature.com/articles/d42859-019-00010-6, where the study highlights that the most cruial point of our immunoligical development with a microbiome happens post-natal. The article compiles research from England, France, and Nigeria, showing how there were varous studies that tested the difference in how these children were fed. Further promoting the idea that infants build a succession of a microbiome, and not endowed with them. In as early as 2-3 years, the infants develops a microbiome nearly identical to that of an adult, regardless of mode of delivery. In the long run, the delivery does not have much of an effect.