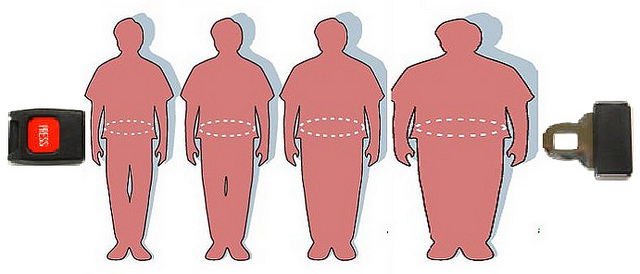

Adolescent obesity is a significant public health concern in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the percentage of adolescents aged 12–19 years who were obese increased from 5% in 1980 to nearly 21% in 2012. Unchecked obesity places teenagers on a trajectory for a variety of health issues — diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, several types of cancer, and osteoarthritis — as they grow older.

In 2010, the National Center for Children in Poverty developed recommendations for local, state, and federal policymakers to combat the adolescent obesity problem and reduce its impact. One of the many recommendations was to limit childhood exposure to food marketing, as food advertising had been shown to strongly affect children’s food habits.

Image credit: Mike Licht, CC BY 2.0

Now, results from a new study focusing on the 12 – 16 age group (Individual Differences in Reward and Somatosensory-Motor Brain Regions Correlate with Adiposity in Adolescents) show that TV food commercials disproportionately stimulate the brains of overweight adolescents when compared to healthy-weight adolescents. The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging to examine the brain responses to two dozen fast food commercials and non-food commercials, which were embedded within an age-appropriate show, “The Big Bang Theory.” The participants were unaware of the study’s purpose.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging — a safe and noninvasive technique — measures and maps the activity of the brain by detecting changes in blood oxygenation and flow. Active areas of the brain consume more oxygen, resulting in increased blood flow. Thus, the technique allows to generate a map showing the regions of the brain involved in specific mental processes.

The researchers found that, compared to non-food commercials, food commercials more strongly engaged regions involved in attention and focus (occipital lobe, precuneus, superior temporal gyri and right insula), and in processing rewards (nucleus accumbens and orbitofrontal cortex.) Adolescents with higher body fat showed greater reward-related activity than healthy-weight teens in the orbitofrontal cortex and in regions associated with taste perception.

Most surprisingly, in overweight adolescents, food commercials also activated a brain region that controls the mouth. Kristina Rapuano, lead author of the study, said in a press release: “This finding suggests the intriguing possibility that overweight adolescents mentally simulate eating while watching food commercials. These brain responses may demonstrate one factor whereby unhealthy eating behaviors become reinforced and turned into habits that potentially hamper a person’s ability lose weight later in life.”

In the published paper, the authors point out that the adolescents involved in their study reported watching an average of 5 hours of TV per week, well below the 4 hours/day of TV viewing estimated by national surveys. Thus, future studies should aim to include participants that more closely represent the national average in terms of media use and other possible confounding variables, as for example socioeconomic status.

How can results from this study guide the design of intervention strategies based on diets? Rapuano said in the press release: “Unhealthy eating is thought to involve both an initial desire to eat a tempting food, such as a piece of cake, and a motor plan to enact the behavior, or eating it. Diet intervention strategies largely focus on minimizing or inhibiting the desire to eat the tempting food, with the logic being that if one does not desire, then one won’t enact. Our findings suggest a second point of intervention may be the somatomotor simulation of eating behavior that follows from the desire to eat. Interventions that target this system, either to minimize the simulation of unhealthy eating or to promote the simulation of healthy eating, may ultimately prove to be more useful than trying to suppress the desire to eat.”

However, another possible intervention strategy is one of the many recommended by the National Center for Children in Poverty: “By limiting advertisements for unhealthy foods targeting young people, policymakers can make it more likely that adolescents will make healthier decisions about food.”